Christmas-themed Transformers stories are comparatively rare, and perhaps that’s why the ones that do exist tend to linger in the memory a little longer. Yet even among that small number, there’s one that has always stood out for me as something rather special.

Published in Marvel UK’s The Transformers #250 and cover-dated December 1989, The Greatest Gift of All is a short black & white B-story written by Simon Furman, with art by Staz Johnson. It arrived right at the end of the decade, at a point where the UK comic’s exclusive material was about to move away from its long-running ties to the US continuity, and it also had the distinction of being the last non-prose Christmas strip Marvel UK would ever publish. A small footnote, perhaps, but a poignant one all the same.

More importantly, though, it’s a story that feels inherently tied to Christmas without ever needing to lean on decorations, festivities, or seasonal gimmicks. Instead, it offers something far more reflective: a quiet meditation on responsibility, choice, and what it truly means to do the right thing. These are all tribulations that Marvel UK’s depiction of Optimus Prime would regularly struggle with, but they’re never better exemplified than here. It’s also one of the reasons I’ve long associated Powermaster Optimus Prime with Christmas — something we recently touched on again during a Triple Takeover minisode discussion about that specific iteration of the character.

So today, let’s take a closer look back at why The Greatest Gift of All still resonates all these years later.

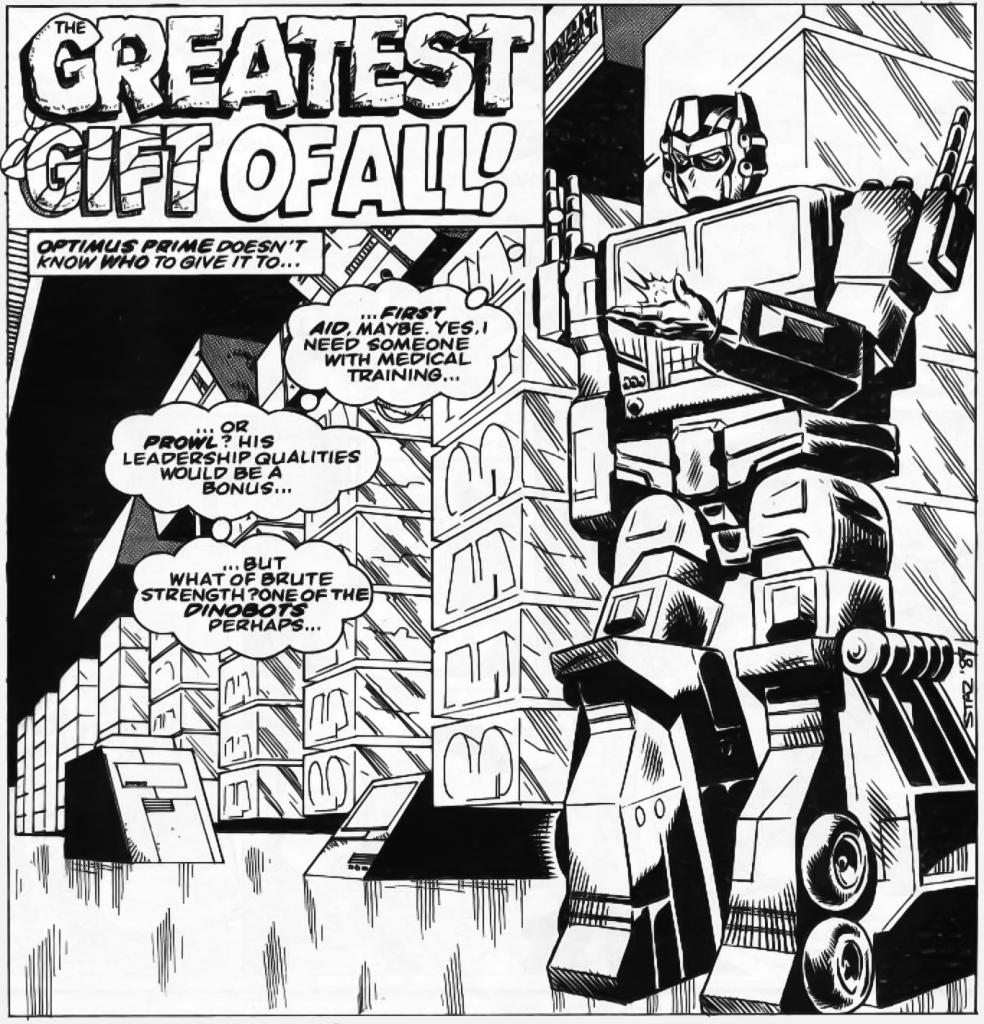

#5: Optimus Prime’s dilemma is painfully human

At the heart of the story is a simple but agonising problem. Optimus Prime has come into possession of a fragment of the Creation Matrix, granting him the ability to restore life to one of the many fallen Autobots stored in stasis. It’s an extraordinary power, and one that immediately weighs heavily upon him.

He considers the options carefully: First Aid would be invaluable as a medic; Prowl’s leadership could steady the ranks; one of the Dinobots might provide much-needed strength. Each choice is rational, and each is defensible, yet none of them sit right in Optimus’ mind.

What Furman captures so well here is that sense of paralysis that comes not from lacking options, but from having too many to reasonably justify. Optimus isn’t paralysed by indecision because he doesn’t care — quite the opposite, he cares too much. The very act of choosing feels wrong, because to choose one life over another is to pass judgement in a way he isn’t comfortable with.

It’s a wonderfully human reaction, and one that immediately grounds the story emotionally.

#4: A refusal to play god

Optimus briefly toys with the idea of making the decision arbitrarily, even settling on Seaspray simply to remove intent from the process. Yet that, too, feels hollow, as randomness doesn’t absolve responsibility — it merely disguises it.

This is where The Greatest Gift of All really begins to distinguish its version of Optimus Prime from the many interpretations that would follow. This isn’t a flawless, preordained leader who always knows the correct course of action; instead, it’s a character who actively recoils from the idea of wielding absolute power, recognising that the act itself is the problem.

It’s a depiction that many long-time fans still regard as definitive. Marvel UK’s Optimus wasn’t special because he was perfect — rather, because he grappled with his choices. He questioned himself, wrestled with the consequences, and ultimately chose restraint not because it was easy, but because it was inherently ethical. To paraphrase philosopher Aldo Leopold’s words, ethical behaviour is doing the right thing when no one else is watching, and for an entire generation of kids who grew up with these comics, we saw that perfectly demonstrated in the way our version of the heroic Autobot leader chose to conduct himself, even when it was a tough choice to do so.

That internal conflict is a huge part of why this version of the character continues to resonate.

#3: War shown through consequence, not spectacle

Optimus’s philosophical dilemma is interrupted by conflict elsewhere, as the Micromaster Rescue Patrol corners the Decepticon Whisper, triggering an aerial assault that devastates the surrounding forest. Yet what’s really striking here is how the scene is framed.

There’s no triumphant battle choreography or over-the-top bombast, which all too often is a staple Transformers media can fall back on. Instead, Optimus monitors the engagement remotely, issuing orders that no harm should come to human or animal life. The real gut punch arrives not through the combat itself, but via the computer readout that follows — a cold, clinical assessment of the environmental damage caused as a by-product of the fighting.

For a toy tie-in comic published in the late 1980s, this is quietly radical stuff. The war isn’t glorified or celebrated; instead, attention is drawn to the collateral damage, the scars left behind, and the dawning realisation that this destruction has been happening all along, largely unnoticed.

It’s an unmistakably anti-war sentiment (and, for what it’s worth, a strong eco message, too), yet one delivered without preaching, and it arguably lands all the harder for its restraint.

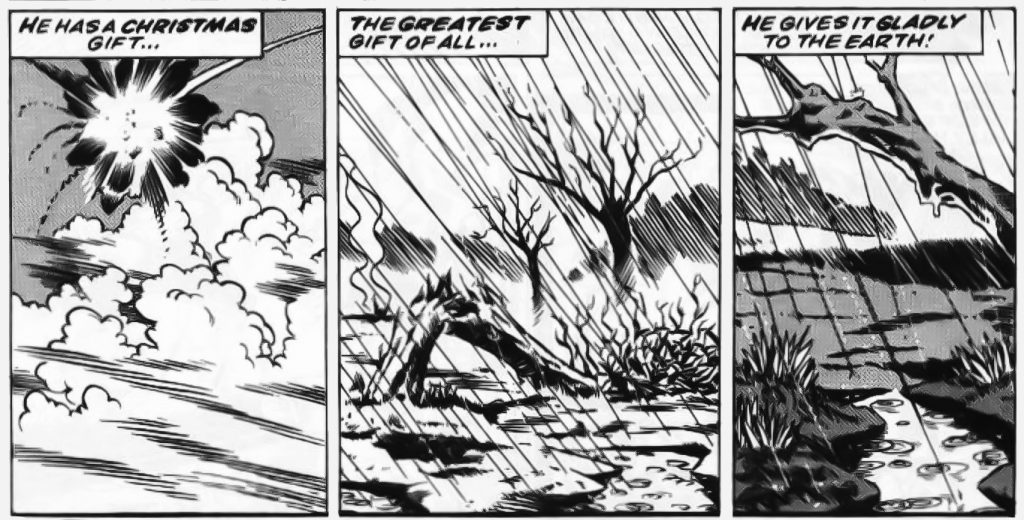

#2: Choosing to heal rather than resurrect

This realisation becomes the turning point of the story. Optimus recalls the Rescue Patrol, not to secure a tactical advantage, but because he finally understands the wider cost of the conflict, and with that understanding comes clarity.

Rather than use the Creation Matrix fragment to revive a single Autobot — no matter how worthy — he instead sends it into Earth’s atmosphere, where it manifests as life-giving rain that repairs the damage inflicted upon the environment. It’s a beautiful choice, and a selfless one: a gift that asks for nothing in return.

In refusing to resurrect one life, especially that of one of his beloved comrades or friends, Optimus instead chooses to preserve countless others, restoring balance and offering a sense of atonement. It’s a decision rooted not in strategy or sentiment, but in humility, and it’s hard to imagine a more fitting expression of what Christmas is meant to be about, or something more quintessentially Optimus Prime.

#1: A perfect example of what Transformers can be

Ultimately, The Greatest Gift of All endures because it understands something fundamental about Transformers when it’s at its best. The main characters may be robots, sure, but they’re depicted in a manner which reflects back on us, as readers. Beneath the hardware, the factions, and the endless war, the franchise has always had the potential to explore profoundly human ideas — empathy, responsibility, and sacrifice.

Yet this story doesn’t shout about those themes; it whispers them. It trusts the reader to pick up on the nuance, to sit with the discomfort of Optimus’s dilemma, and to appreciate the quiet strength of his final choice. The final message of the piece sits as an inherent blueprint for how to conduct ourselves in the face of such hard choices, rather than as a preachy moral sermon delivered in a manner that is all too on-the-nose.

That it does all this while also serving as the last Marvel UK Christmas strip only adds to its gentle melancholy. There’s no grand farewell and no spectacle, just a thoughtful pause and a reminder of what made this era of Transformers storytelling so special, demonstrating perfectly why this comic still means so much to fans who grew up with it.

It’s no wonder that, for many of us, this version of Optimus Prime, in his Powermaster form, feels intrinsically tied to Christmas. Not because of presents or pageantry (although the corresponding 1988 toy did reflect that, too!), but because of what the character represented for us: reflection, humility, and the idea that sometimes the greatest gift of all is knowing when to make the right choices, even if they’re the hard ones.

And really, isn’t that a lesson worth revisiting at this time of year?

TTFN